|

| Daguerreotype in original case. Made of wood with a leather cloth covering and a velvet interior. It has protected the delicate image surface well. |

Seriously, Daguerreotypes of nudes are rare and highly sought after by collectors. This gentleman is much more typical of the kind of genre portraiture of the 1840s-50s. His head is probably in a brace, which while not actually clamping him in position would probably be uncomfortable or disconcerting, hence his expression. It reminds me of the wonderful scene in Mike Leigh's "Mr Turner" when Timothy Spall as Turner encounters the "Daguerrian Artist" JJE Mayall:

|

| Mr. Tuner (Timothy Spall) poses for a Daguerreotype. The object on the right is a mirror to light his face. |

|

| JJE Mayall (Leo Bill) timing the exposure with a pocket watch. |

The whole film is terrific but (obviously) I particularly enjoy this scene which shows Turner as interested in the then newfangled process of photography but grumpily sceptical. This has some basis in fact as Turner did know Mayall, sitting for portraits and discussing photography with him on several occasions.

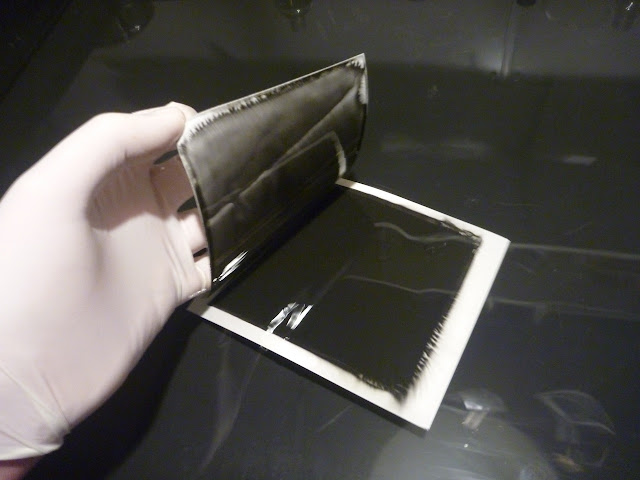

Anyway, back to my Daguerreotype. I acquired it with no known provenance so there's no way of knowing who the gentleman is. It was in the usual covered wooden case which had split in the usual way(!) along the hinge. Most of these cases rely on the leathercloth covering forming the hinge between the two halves rather than a metal fitment and they eventually wear out. The condition of the image was very good but the cover glass was filthy and there was a lot of dust and debris on the inside surface as well as the plate itself.

The usual advice to anyone thinking of taking a Daguerreotype apart is "Don't!" They are very delicate and repair or restoration work is best left to a specialist restorer. I'd agree with this if the image is especially valuable such as a portrait of a family member, though any image which has survived for over 150 years should be cherished. What follows therefore is NOT meant to be a 'how to..' guide to Daguerreotype restoration but just for interest to see how they are put together.

The case is made of wood, covered in a kind of leathercloth (actually a kind of leather-textured paper or fabric) material. The image side has a velvet border which holds the plate, mount and cover glass in place. On this one they weren't fixed in place and very careful levering with a scalpel lifted them out.

The three layers are important. The glass protects the surface from touch, atmospheric pollutants, damp and dirt. The mount keeps the glass from touching the plate and the plate itself is sealed around the edges with paper tape to keep the whole image area in its own little micro-climate. If this is all intact then don't mess with it. In this case the paper tape had entirely disintegrated, with bits falling down onto the image surface. The lack of a seal around the edge meant that dirt and velvet fibres were also free to fall in and obscure and possibly damage the plate.

After cleaning the glass with warm water (I didn't use a cleaner as solvents can remain and attack the image) and wiping the metal mount it was time to look at the image itself.

A Daguerreotype image is incredibly delicate. If you touch the plate surface it's perfectly possible to wipe the image off completely. It's easy to leave residue from skin etc. or microscopic scratches so however much crud there might be on the surface the advice is don't touch it with anything!

The Contemporary Daguerreotype artist community website: http://cdags.org has a whole section on repairs and cleaning if you're actually contemplating it.

I wouldn't even dare use a canned air blower or my own breath to remove dust: Both can contain moisture or chemicals which deposit on the surface. I used my Giotto "Rocket" air blower as used on digital sensors as it just blows the ambient air around.

Here's the bare plate after dusting. There's a fleck of something on the shoulder which has left a red stain on the plate- possibly the copper coming through (Daguerreotypes are made from a copper plate with a thin electroplated layer of silver on top) but the blower wouldn't shift it. I resisted the urge to poke at it and left it alone. The rainbow effect is characteristic of this process and as it follows the shape of the mount it's clearly caused by either light or chemical effects (the mount is a gold coloured metal). It looks very beautiful but actually represents deterioration.

In the copy photograph above the colour is a little exaggerated but it shows that this image was originally hand coloured. There's a little rosiness to the gentleman's cheeks and his hand. The blue colour of the background might be hand tinting but light areas often acquire a blue tint through a sort of solarisation so it's hard to say. The plate appears to have been hand cut with shears (see the top left corner) and the edges are bevelled slightly. I don't know if this was done with some kind of press or if it's an effect of the polishing process. Bevelled or curved edges would make it easier to polish a small thin plate like this on a buffing wheel with less risk of the eyes catching and distorting the plate.

This is one of the tests of a true Daguerreotype. Seen from an oblique angle the image becomes very silvery and as a negative. The reddish stain on the shoulder shows up well here. Here's a very short video clip showing the effect.

Note that it's easy to confuse a Daguerreotype with an Ambrotype, and a lot of the ones on Ebay etc. are mis-labelled. Only if it can be viewed as almost mirror-like and as a negative image will it be a genuine Daguerreotype.

Once I was sure the cover glass was completely dry I reassembled everything, re-sealing the edges with archival paper tape. The difficulty with this kind of frame is that the edges are visible so the tape can only be stuck to the edge of the glass and the back of the mount. The velvet holds it all firmly in place at least so no more glues than those in the tape are needed. It's all reversible (the tape can be removed if dampened with water) which is what proper conservators prefer.

A Daguerreotype is a wonderful thing: a crystalline, delicate silvery thing which appears as if painted by fairies more than a mechanical, technical process. I'm fascinated too by the mystery of the sitter: Who was he? Is this the only picture of him ever made? Where did he live? How? and when? We can never really own these pictures: We are simply custodians for the next generations.