The Method:

Carbon is a transfer process. The light sensitive emulsion is coated onto a support sheet called the "tissue" which is contact printed under UV light. The tissue is then mated to the final print material and allowed to bond. The gelatin-based emulsion is then softened in warm water until the tissue backing can be removed and the image 'developed' by rinsing away the soft unexposed areas of the emulsion leaving an image made from microscopic carbon particles.

|

| These gentlemen are variously squeegeeing, developing and finishing carbon prints in this illustration from the Autotype Co. book (see below) |

Sounds easy doesn't it? As soon as you start researching however it quickly becomes a lot more complicated. Most of the 'Alchemy' involves making the tissue: A tricky mixture of carbon black or Indian ink in gelatin, coated onto a substrate which needs to be microporous but not too absorbent, strong but flexible, water resistant but soakable etc. etc. - and that's before you get to coating the stuff! It's potentially messy; the carbon particles can be as fine as cigarette smoke so weighing the dry powder out is a nightmare apparently. The gelatin-carbon solution is known as the "glop" so you can tell what sort of consistency that has. There's lots online and in manuals on how to make carbon tissue, and like so much of the Alt. process world it's full of conflicting advice with everyone (it seems) insisting their method is the Only True Way.

Carbon tissue used to be widely available commercially. The Autotype company was founded in 1868 by Sir Joseph Swan (co-inventor of the light bulb) and it flourished for decades selling a wide variety of different types and colours of carbon tissue for photographic use.

The company still exists. These days it makes specialist film products for the graphic arts industry and computer and 'phone screen coatings. - but sadly no carbon tissue.

Bostick and Sullivan

US readers will be familiar with the company of Dick Bostick and Melody Sullivan. For years they have been supplying photographic and alternative processing materials, in roughly the same way as Silverprint in the UK. One of their long-term projects has been to re-manufacture carbon tissue commercially and they now sell it through their website: https://www.bostick-sullivan.com

It's available in three colours, black, brown and green.

The only downside is that the shipping costs to the UK are VERY high: - It cost me around £160 in total to get two pieces of tissue sent. It's only supplied in rolls 3 feet wide x 4 feet long and while that makes the use of the tissue economic it does push up the shipping costs! We shall have to see if we can do anything about this..

First tests with B+S tissue.

The B+S carbon tissue is an excellent product. A beautifully consistent coating on a (reasonably) well behaved backing. It does curl a bit when wet but not excessively. It's not light sensitive as supplied which means it's easier to handle and trim to size in the daylight. You only use pieces the same size as your negative and I found it simplest to cut a set of sheets to exact size before sensitising. any offcuts can be used for test strips.

Sensitising.

To make the tissue light sensitive it needs to be coated in a weak solution of potassium dichromate. Dichromates are nasty things: Hazardous to health and not good for the environment. The actual solution isn't excessively dangerous as it's only used in concentrations of 0.5% to about 4% max but the raw chemical should be handled with great care, particularly to avoid breathing the dust or getting it on the skin. Once mixed (in a solution of distilled water and isopropyl alcohol) it should still be handled with gloves. Goggles are a good precaution too.

The dichromate is brushed onto the tissue surface with a foam brush and then left to dry in a dark box. Once dry it needs to be used within a day or two as it goes 'off'. though you can apparently freeze it to preserve it.

Exposure.

The tissue needs UV light to expose it so I used my light box. It's quite slow: I found I needed exposures of between 2 and 16 minutes with most negatives. Camera negs tend to be rather too 'flat' for the process so digital negs are really the best way to go. Contrast can be adjusted by altering the dichromate strength but it's not a big range.

Mating the tissue to the support.

The carbon image is only carried by the tissue. It needs to be transferred to the final paper support. While it is possible to coat almost anything (watercolour papers are popular and carbon on opal glass pictures were made around the 1900s) the can be tricky so I followed recommendations and used fixed out photo paper. This is ordinary black and white enlarging paper which has been fixed, washed and dried to remove the silver and leave a suitable gelatin coated paper. Inkjet materials are also recommended as their microporous surfaces are designed to hold the ink. The gelatin carbon emulsion sticks equally well.

The mating process is easy: a quick dip of both tissue and support in cold water, a brush to remove bubbles and then the two are placed face to face, removed and pressed together with a rubber squeegee.

The squeegeeing removes the excess liquid from between the surfaces and generally that's all that's needed to hold them together. If they curl, put a sheet of glass on top. The mated pieces are left for at least 15 minutes (some recommend much longer) to bond.

Development.

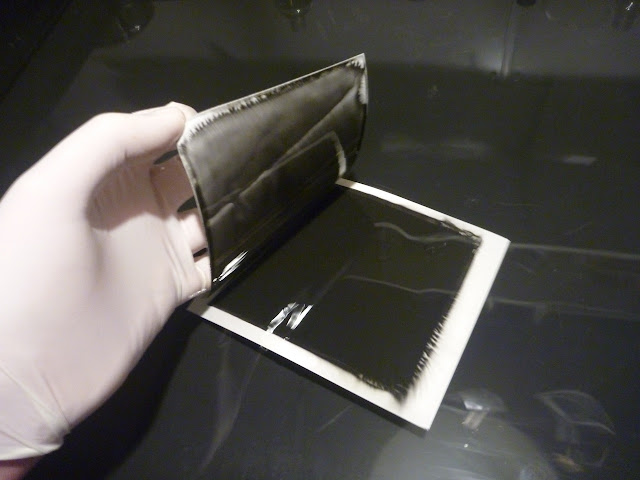

No chemicals are needed, just water at around 38 degrees C to soften the gelatin. The print is placed in a big tray of warm water and allowed to soak there for at least 5 minutes. After that, the tissue (top piece here) can be gently peeled away.

The carbon emulsion is soft and soluble in the highlights and harder in the shadows where it's received more light. Development consists of rinsing away the soft unexposed areas to reveal the image. Above you can see the pigment flowing off the surface in the bottom corner.

As the emulsion is not light sensitive when wet, development can be carried out in normal light. Keep gently agitating the print under the warm water and the image will appear:

Above you can see the image starting to appear. The carbon particles look like ink in water.

Development is complete when no more black runs off the surface. The image is very fragile at this stage: You can see it's started to peel off at the bottom. Putting a dark border around the neg helps avoid this as there's then a hard black-white edge which dissolves less.

Once developed the print should be rinsed in cold water to harden the gelatin and dried. Once dry the image surface is more robust and if using glossy papers you can often see a texture. The dark parts are physically thicker than the light parts and this is visible, even when the print is dry.

Conclusion

If you use ready-made carbon tissue the process is not too messy or difficult to do. Inkjet or fixed-out photo papers are recommended for initial trials as the emulsion (mostly!) stuck well to these. Other materials may need 'sizing': - coating with other substances to encourage the gelatin to stick properly. I've used the Silverprint Alum/gelatin subbing solution for other things in the past: This might be worth a try?

The biggest thing is negative contrast: To get prints which do the process justice the negative has to have a density/exposure curve which corresponds to the carbon emulsion. This is quite long and with little or no appreciable 'toe' or 'shoulder' as far as I can see. I made some tests with some test negs supplied by Beytan Erkmen as they had more overall contrast than my camera negs, but they still had problems with local contrast. I'll do some more research into suitable neg curves and see what might work.

EXPERIMENTING SESSION

(I won't call it a workshop as I won't really be teaching stuff). - I shall do a session in UCA Farnham soon (January 2017 I hope) when we can have more of a chance to experiment together. I have a few health & safety hoops to jump through first but as soon as we've done all the necessary risk assessment stuff and found a suitable day I'll let you know.

Note that this is a Alt. Process User's Group session and not a taught UCA one so it's open only to members/authors on this site. If you're interested in coming along, email me!

No comments:

Post a Comment